Repatriation of Indigenous Sacred Bundles: Kímmapiiyipitssini

Dear Researchers - Here is the product of a little bit of research I completed over the summer. Overall, I’m happy with it.

Introduction

In this time of Truth and Reconciliation in Canada, it can be difficult to know what any individual or organisation can do to contribute to a meaningful path forward.

Museums are in a unique position as cultural preservers and sources of knowledge. They are places at which bridges are constructed between different cultures and communities. Our evolving focus on Truth and Reconciliation provides museums and their governing boards with an excellent opportunity to usher Canadians into a new society in which indigenous people and their culture are respected and honoured.

One high-profile collection for many museums is that of indigenous sacred objects. While there are many, many types of these objects, one is particularly fascinating and poignantly relevant - the sacred medicine bundle.

Description of Medicine Bundles

Medicine bundles, or sacred bundles as they are also known, have significant ceremonial and religious value and are a source of spiritual healing and protective power for their owners. Traditionally most bundles have individual owners or belong to a family, but some are owned by entire communities.1 Sacred bundles are a combination of historical record and powerful spiritual energy source for future endeavours. As explained by Curator and Archivist Dennis Slater, a sacred bundle is a “…living thing, like a battery”2 that, when maintained correctly, restores and energises the community of which it is a part.3

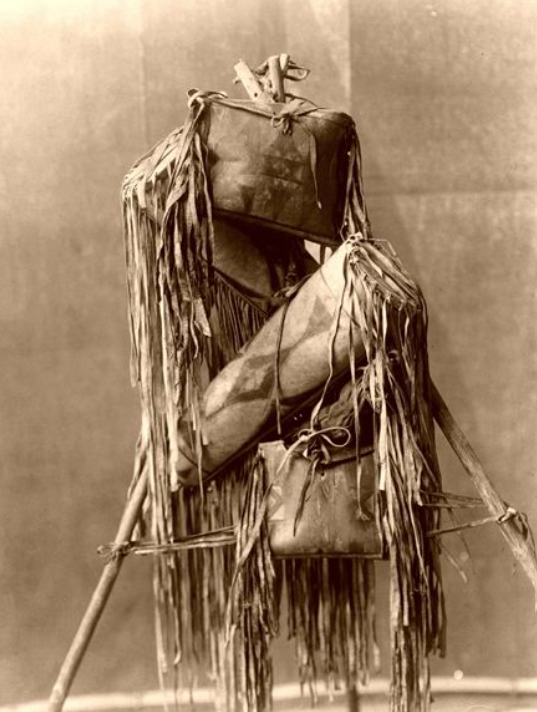

A sacred medicine bundle is a collection of objects kept together typically in a rawhide wrapping. The objects vary from bundle to bundle, but often are items like feathers, paint pigment, animal skins or bones, dried medicinal plants or roots, tobacco pouches, and more significant pipes.4 This isn’t an exhaustive list. An individual bundle will contain objects of significance for its owner and will vary depending on the lived experiences of the owner or the community. The correct use of a bundle requires wisdom and specialised, often secret, knowledge.5 Sometimes this knowledge is spread amongst several individuals, so that a ceremony will require multiple participants to participate in the ritual.6

Peigan Medicine Bags, Edward Curtis, 1910

In addition to specific rituals required for use of these bundles, there are certain requirements for a bundle’s storage. For example, the Cheyenne River Sioux kept their last known White Buffalo Calf Pipe bundle in a rectangular log structure that has no windows or other opening save for a small doorway on the east side.7 The bundle was the only object kept in the building and the floor was regularly swept.8 The bundle itself was draped in a buckskin hood, kept on a tripod, and grey seed-sage is placed on the floor directly under the bundle. The position of the bundle was changed twice a day in order for it to continually face the sun.10

Full knowledge of sacred bundles, their significance and use, outside of indigenous communities is not possible, however, they have been studied by anthropologists and archivists11 for over a century and held by museums for just as long. As bundles are passed down from generation to generation, so too are the ceremonial rituals and songs required for their use. “To open or use a bundle without the proper ritual and ceremony would invite disaster.”12 During the research for repatriation of a medicine bundle, Slater learned of the traditional knowledge required to open and use a bundle. For example, several ties holding the bundles together are knotted, and to open and use a bundle each knot may require several stories and songs as it is untied.13

Medicine bundles have been a part of indigenous life for centuries, but known to colonialist culture for only a short time. When these sacred bundles are removed from their families or communities, their context and knowledge about them is lost.

Medicine Bundles in Museums

Sacred bundles are often part of high profile ethnography collections in museums.14 As with most other artefacts, museums have varied paths to acquisition and accession. In some cases, such as a Pawnee sacred bundle donated to the Kansas State Historical Society15 bundles were brought to the museum by the indigenous owner when they could no longer care for them. The Pawnee bundle was first offered to the donor’s sisters and daughters but they demurred.16

In contrast, some indigenous artefacts including sacred bundles, were acquired with less integrity by the museums in which they currently reside. For example, in Saskatchewan in the 1960’s several museums sent representatives to purchase indigenous artefacts from various Treaty 4 and 6 Nations.17 At this time, most first nations communities in this area (and many others) were suffering impoverished economic conditions, addiction issues, and domestic abuse. These circumstances are understood today as the legacy of intergenerational trauma caused by the residential school programs and other practices of cultural genocide. Arguably, artefacts purchased from indigenous families and communities in this time and place were acquired from the donors under duress. More sharply, these acquisitions were tantamount to appropriation. Compounding this inauspicious accession method was a lack of respect for indigenous history and culture, which was then lost when the artefacts were separated from their people. Regardless of the circumstances in which these artefacts were acquired, they became the property of several museums in western Canada.

As mentioned in the introduction, museums exist as institutions of education and cultural preservation. However, it is increasingly difficult for museums to distance themselves from the sometimes unscrupulous methods of acquisition as well as the fact that artefacts like sacred bundles are often being held in inappropriate settings by an administration that does not have all the knowledge and wisdom to properly care for them. Not all sacred bundles were acquired by museums through subversive means, as demonstrated by the story of the Pawnee bundle above; however, it is imperative that we ask who is being served when sacred bundles are on exhibit or in archive storage in museums today. When the specialised and sometimes secret knowledge of an object is unknown to the curator, the context and the story behind an artefact is inaccessible. When this is the case, museums lose their educational role and fail in their attempt to preserve indigenous culture.

Making the Case for Repatriation

In 2007 the United Nations (UN) recognized worldwide destruction of indigenous culture. In an attempt to mitigate the inherent loss and devastation resulting from this phenomenon the UN passed the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP).18 While not legally binding for any nation, this declaration promotes rights of indigenous cultures and outlines the role of individual states in helping indigenous people to achieve equality and protect cultural diversity. Specifically, UNDRIP espouses “…minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world.”19

Rights espoused in the UNDRIP include:

…[T]he right not to be subjected to forced assimilation or destruction of their culture, …[and] the right to practise and revitalize their cultural traditions and customs. This includes the right to maintain, protect and develop the past, present and future manifestations of their cultures, such as archaeological and historical sites, artefacts, designs, ceremonies, technologies and visual and performing arts and literature.20

Initially Canada, along with the United States, New Zealand, and Australia opposed the UN declaration.21 The Canadian opposition was ostensibly based in a claim that UNDRIP provisions are incompatible with the laws enshrined in the Canadian Constitution.22 The most “…controversial feature [was considered] a call for ‘free, prior, and informed consent’ (FPIC) by Indigenous peoples before economic development projects can take place on lands they inhabit or to which they may have a claim”.23 It is worth noting here that from early in Canada’s legal history the constitution has been described as a living tree, to be a predictable foundation of law while at the same time be interpreted in ways to evolve with our society through the passage of time.24 In other words, the initial opposition to UNDRIP was arguably more ideological than constitutional.

In 2010, Prime Minister Harper changed course and acknowledged UNDRIP as a non-legally-binding “statement of aspirations”.25 Twelve years later, the federal government under Prime Minister Trudeau passed Bill C-15, creating the UNDRIP Act.26 This legislation “…recognizes the inherent right to self-determination and affirms UNDRIP as a source for the interpretation of Canadian law.”27

The federal UNDRIP Act does not directly apply to Canadian museums, however it is an indicator that our society is at a pivotal and transformative moment in recognizing and respecting the rights of indigenous people and their culture. The implementation of UNDRIP was recommended by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada, which was formed as one of the outcomes of the largest class action settlements in Canadian history to facilitate reconciliation in the aftermath of the residential school system.28 In the TRC’s final report, published in 2015, are 94 Calls To Action for all levels of government to work in the areas of child welfare, education, health, justice, language and culture to repair damage done by the residential school system.29 Of particular interest to Canadian museums is Action 67:

We call upon the federal government to provide funding to the Canadian Museums Association to undertake, in collaboration with Aboriginal peoples, a national review of museum policies and best practices to determine the level of compliance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and to make recommendations.30

Action 67, combined with a reading of UNDRIP Article 11 (which includes the right of indigenous people to maintain and protect their artefacts), appears to create a path for the funding of UNDRIP-compliant policy and best practice doctrine. The return of artefacts such as sacred bundles to the communities from which they came is a clearly definable practice that should be a priority for museums in the creation of UNDRIP-inspired best practices. While the return of many indigenous artefacts would help us on our collective path to reconciliation, sacred bundles, and in particular medicine bundles, are a poignant example of a gesture that embodies an actionable desire to provide healing for indigenous cultures.

Case Study

In an interview with Dennis Slater, former Curator at the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Alberta, he describes the process of returning a Káínai medicine bundle in southern Alberta.31 This return occurred in the 1990’s, long before UNDRIP and the 94 Calls to Action existed. In a forward-thinking decision, the Chief Curator of the Glenbow resolved to repatriate the Káínai bundle. At the time, it was difficult to convince museum governance that in spite of the Glenbow’s clear legal ownership of the medicine bundle, the question of true ownership persisted.32 Additionally, it was difficult to establish a dialogue with the Káínai community.33 Before the return of the medicine bundle, the Glenbow Museum was an institution outside of the Káínai community without any contacts within. This difficulty was compounded by the fact that the Káínai could justifiably view the museum with distrust, given that the museum’s holdings included a medicine bundle from their community that they had not been able to access for decades.34

After months of communication with a Káínai Elder, a relationship was built, and enough guidance and advice was given to the museum staff to enable a return. During the course of a year, the medicine bundle was taken to the community three times and brought back to the museum and finally returned on the fourth visit.35 Each visit involved ceremony and performance of rituals, and the bundle had to be cared for with very specific instructions when it made the journey back to the museum each time. Four trips were required because in indigenous communities in the Treaty 7 region where the Káínai reside, four is a sacred number, hence the four visits before the medicine bundle could be returned.36 In the final return visit, the museum staff took part in a sweat lodge ceremony during which the Elder recited poems and sang songs. The bundle was placed above the sweat lodge, over the opening, and turned by two Káínai women at various points in the ceremony.37

The effort and expense was necessary in order to return the bundle with restored energy, and not simply return an artefact that was simply an inanimate object that had been stored for decades on a shelf in a museum’s archives. It is not merely the returning of the artefacts that is important, but returning them in a way that is respectful of indigenous culture and spiritual beliefs.

Further examples of repatriation provided by the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia can be found here.

Repatriating Medicine Bundles

The path to reconciliation is going to be a long and arduous one, with a great deal at stake. The relationship between indigenous people and the rest of society, including governmental institutions, is understandably fraught with mistrust. The 94 Calls to Action help to add clarity to this complex situation. As outlined above, Canadian museums have a clearly defined role to play, should they accept it.

The fact that sacred bundles exist in many museums’ holdings was likely not a result of purely careless or rapacious intent. Most in the museum community want to promote and celebrate indigenous culture. We can now understand that holding sacred bundles is not the way to respect and understand indigenous culture. The cultural devastation suffered by indigenous people in Canada cannot be undone. However, there is a possibility to foster remediation by returning these vessels of healing energy to their homes.

Perhaps along with the return of medicine bundles to their people, museums could get permission from indigenous communities to hold replicas. If a bundle could be studied with respect and integrity, and reproduced in a way acceptable to the true owners of the bundles, these could be more impactful to a museum’s public than the original bundle. Non-indigenous museum patrons could learn far more about indiginous culture if given an explanation as to why the original bundle is not on display - because it is sacred, and like a child, belongs and lives with its people. Indeed, knowledge has been lost, not gained, through the removal of sacred bundles from their communities. If we change the colonialist definition of ownership, we become free to build new relationships and create balance where it was previously lacking.

With a renewed focus on indigenous artefacts, one that embodies a sincere desire for dialogue, trust, empathy and kindness - kimmapiiyipitssini - museums are in a position to lead on the path to reconciliation. As demonstrated earlier through the description of the shift in the federal government’s approach to UNDRIP, we have changed as a society. In fact, with or without federal funding, if museums do not begin to include repatriation of indigenous artefacts in their best practices doctrines, they will be left behind.

Notes

- Diane Good, “Sacred Bundles, History Wrapped Up In Culture,” History News vol. 45 No. 4 (1990, p.13.

- Dennis Slater (Retired Archivist and Curator) in an interview with the author, August 2022, 19:10.

- Ibid., 4:09.

- Ibid., 4:24.

- Ibid., 36:1.

- Ibid., 4:32.

- Sidney Thomas, “A Sioux Medicine Bundle,” American Anthropologist, N.S., 43: (1941), p.605.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Clark Wissler, “Blackfoot Bundles,” Anthropological Papers of the Museum of Natural History, Vol VII Part 2 (1912).

- Good, p.14.

- Slater, 4:24.

- Ibid., 0:51

- Good, p.14.

- Ibid.

- Slater,14:05.

- United Nations, “Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,” Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2007, https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html.

- Ibid., Article 43, p.28.

- Ibid., Articles 8 and 1, pp. 10-11

- Fraser Institute, “Squaring the Circle: Adopting UNDRIP in Canada,” 2020, https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, para.1.

- Ibid.

- UNDRIP Act, S.C. 2021, c.14.

- Sander Duncanson, Coleman Brinker, Maeve O’Neill Sanger, Kelly Twa, “Federal UNDRIP Bill Becomes Law,” Osler, Osler Hoskin and and Harcourt LLP, 2022, https://www.osler.com/en/resources/regulations/2021/federal-undrip-bill-becomes-law#:~:text=On%20June%2016%2C%20Canada's%20Senate,the%20Act)%2C%20into%20law, para 4.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p.8.

- Slater, 2022.

- Ibid., 1:45.

- Ibid., 2:04.

- Ibid., 3:53.

- Ibid., 6:45.

- There are four seasons, four directions of the compass, four human needs - physical, spiritual, emotional and intellectual, and four kingdoms - animal, plant, mineral, and human; “Medicine Wheel and the Four Directions,” Legends of America, 2022. https://www.legendsofamerica.com/na-medicinewheel/#:~:text=The%20number%20four%20is%20sacred,tobacco%2C%20cedar%2C%20and%20sage.

- Slater, 4:09.

Bibliography

Baird, Jill R., Solanki, Anjuli and Askren, Mique’l, eds. “Returning the Past: Repatriation of First Nations Cultural Property.” UBC Museum of Anthropology. n.d. https://moa.ubc.ca/wp-content/uploads/TeachingKit-Repatriation.pdf

Bernstien, Jaela. “Canada’s Museums Are Slowly Starting to Return Indigenous Artifacts [sic].” Macleans.Ca (blog) (2021). https://www.macleans.ca/culture/canadas-museums-are-slowly-starting-to-return-indigenous-artifacts/.

Boutilier, Sasha. “Free, Prior, and Informed Consent and Reconciliation in Canada: Proposals to Implement Articles 19 and 32 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.” Western Journal of Legal Studies 7, no. 1 (2017). https://www.canlii.org/en/commentary/doc/2017CanLIIDocs333?zoupio-debug#!fragment/zoupio-_Tocpdf_bk_1/(hash:(chunk:(anchorText:zoupio-_Tocpdf_bk_1),notesQuery:'',scrollChunk:!n,searchQuery:undrip,searchSortBy:RELEVANCE,tab:search)).

Duncanson, Sander, Coleman, Brinker, O’Neill Sanger, Maeve, and Twa, Kelly. “Federal UNDRIP Bill Becomes Law.” Osler. June 22, 2021. http://www.osler.com/en/resources/regulations/2021/federal-undrip-bill-becomes-law.

Edwards v Canada (Attorney General) [1930] AC 124 at 124, 1929 UKPC 86. Fraser Institute. “Squaring the Circle: Adopting UNDRIP in Canada,” March 10, 2020. https://bit.ly/2TO6fZG.

Gadacz, Rene R. “Medicine Bundles.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Last edited November 19, 2015. ttps://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/medicine-bundles

Good, Diane. “Sacred Bundles: History Wrapped Up In Culture.” History News, American Association for State and Local History, Vol. 45, no. 4, July/August 1990.

Government of Canada. “Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada,” Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs, Administrative page, December 14, 2015. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1450124405592/1529106060525#chp2.

“Implementing of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.” Assembly of First Nations. n.d. https://www.afn.ca/implementing-the-united-nations-declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples/#:~:text=On%20June%2016%2C%202021%20%E2%80%93%20after,Royal%20Assent%20June%2021%2C%202021

Legends of America. “Medicine Wheel & the Four Directions.” 2022. https://www.legendsofamerica.com/na-medicinewheel/

“Living Tree Doctrine.” Centre for Constitutional Studies. July 4, 2019. https://www.constitutionalstudies.ca/2019/07/living-tree-doctrine/.

“Medicine Wheel and the Four Directions,” Legends of America, 2022. https://www.legendsofamerica.com/na-medicinewheel/#:~:text=The%20number%20four%20is%20sacred,tobacco%2C%20cedar%2C%20and%20sage.

Slater, Dennis. Interview by Joanne McKenzie, August 3, 2022. Recording held by author.

Thomas, Sidney. “A Sioux Medicine Bundle.” American Anthropologist. N.S. 43, 1941.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. “Calls To Action.” Government of Canada. 2015. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/british-columbians-our-governments/indigenous-people/aboriginal-peoples-documents/calls_to_action_english2.pdf

Tünsmeyer, Vanessa, “Repatriation of Sacred Indigenous Cultural Heritage and the Law – Lessons from the United States and Canada”, https://www.maastrichtuniversity.nl/news/phd-defence-vanessa-t%C3%BCnsmeyer-repatriation-sacred-indigenous-cultural-heritage-and-law-%E2%80%93

UNDRIP Act, S.C. 2021, c.14.

United Nations. “The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.” Department of Economic and Social Affairs. n.d. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html

Wissler, Clark. “Blackfoot Bundles,” Anthropological Papers of the Museum of Natural History, Vol VII Part 2 (1912). https://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=U_ritzbPZIoC&oi=fnd&pg=PA68&dq=wissler+blackfoot+bundles+anthropological+papers&ots=06kkUTNHqm&sig=a1dBnEE7iCQTA8Ajku9HLL0Y7dc#v=onepage&q=wissler%20blackfoot%20bundles%20anthropological%20papers&f=false